The Jamdani Tradition

Hameeda Hossain

The Jamdani festival celebrates two recent events: UNESCO’s acknowledgement of hand woven Jamdani textiles as an intangible, traditional heritage of Bangladesh and a recognition by the Government of Bangladesh of its Geographical Indicator (GI) status. Jamdani weavers have sustained their tradition of handloom weaving over centuries by maintaining the original mode of production in a concentrated area in Sonargaon. The designs and motifs were created through a fusion of consumer demand, trading systems and weavers’ craftsmanship. Through the centuries, the fabric has travelled from villages around Dhaka across to North India, by land routes to Bokhara and Samarkand and on sea voyages to the Far East, Britain and Europe.

Dhaka was known for 47 different qualities of Malmals – Duriya, Chaharkhanes, Terrindams, Tanzeb and Samadlahar assortments being the most in demand. Jamdani thaans, or figured Malmals, have remained a proud heritage of the weavers of Sonargaon, Rupganj and Siddhirganj in Narayanganj district. It was included in the Mulboos Khas (or annual tribute sent to the Mughal Emperor) by the Nawabs in Bengal. These fabrics were favoured by women courtiers in Europe and England. In modern times Jamdani sarees have become an essential part of a bridal trousseau.

Preserving the Jamdani Tradition

The antique fabrics/sarees displayed at the exhibition have been preserved for over a hundred years by their owners. They are today amongst the finest, extant examples of weaving across the globe. It is remarkable that Jamdani weavers have retained their skills, as is obvious from the replicas displayed at the exhibition. Collections of fine Jamdani fabrics, with very intricately worked designs have been preserved in several museums around the world. Of special mentions are the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, Musee Guimee in Paris, National Museum in Delhi, the Tapi Collection in Surat, Sanskriti Kendra in New Delhi, National Museum in Dhaka, Folk Art Museum in Sonargaon and many more.

For centuries the weaving of Jamdani has been concentrated in some 20 villages in Sonargaon, Rupganj and Siddhirganj. Here the environment, waters of the river Sitalakhya, local markets and ease of communication has allowed for an uninterrupted production. The Jamdani – or figured Malmal – was a world-famous product worn by the Mughals as well as European courtiers. It was known for its unique, geometrical designs, interpreted by skilful master weavers and their apprentices. Jamdani (from the Persian word for flower vase) was also known for its delicate, translucent quality produced with very fine yarn, in which the motifs were interspersed into the weft with a thicker yarn.

Jamdani weaves represent a distinctly traditional culture, which is reflected in its mode of production, its choice of tools, repetition of designs and which have been sustained by trading system over the years. In this craft, master weavers continue to work on pit looms, built with bamboo and string. Jamdani weaving requires two weavers, who sit at the loom. The Master weaver or Guru sings the design instructions (known as a buli) to his shagrid or apprentice seated on his left.

Division of Labour

The division of family labour was very marked in earlier days with women cleaning cotton and spinning yarn on a spindle (charkhi) and children working as apprentices. With economic changes the yarn is now purchased in the market and wound mechanically. Women’s functions have moved as they too work on the loom. The master weavers’ children prefer now to go to schools, so that younger children, who cannot afford school, are recruited from neighbouring areas. Thus, the apprentice system allows for a passing of skills from one weaver to another.

Traditional Tools

At the exhibition are to be found specimens of primitive tools which continue to be used for Jamdani weaving. The natai is used for spinning, the pit loom is strung together with bamboo and strings. The warp is wound on a drum before its threads are passed through a ‘shana’ (or reed). The number of teeth in the shana determines the fineness of the cloth.

Motifs and Designs

Given the simplicity of these tools, it is a marvel that the weaver can produce such intricate designs in high-quality fabrics. The exhibits show the diversity of patterns and motifs created by village craft persons. Individual floral motifs known as buteh are sprinkled along the length, the par or border has different motifs, terchi is a diagonal winding vine like design, and jaal (or net) is a pattern that covers the entire length. Many of these motifs and patterns were fusions of Persian designs reinterpreted by the skill of Jamdani weavers in far-away Sonargaon. They also indicated a creative output of the weavers themselves to simulate local flora and fauna, a favourite being the jasmine flower. The most complex motifs were known as bagnoli (tiger’s paw) or kalka (a paisley). Some of these motifs are to be found in crafts around the world which would suggest a cultural transmission. For example, the kalka or paisley is to be found in Kashmiri shawls and in Scotland where it adopted the name of the town Paisley.

Trading Systems and Markets

These motifs show a timelessness in the art of weaving which is sustained by a generational transmission of artistry. Although folklore ascribes the existence of such weaves to ancient times, historical records are more precise about the role of trade in meeting consumer demand and sustaining this tradition. In the fifteenth century we read of fine thaans (cloth lengths of fine Malmal, coarse Baftas and Jamdanis) carried along the caravan route via Dinajpur, Malda to Bokhara, Ispahan and Samarkand. On the east, they were part of the spice trade moving in ships along the coast as far as Indonesia. Patronage by the Mughals and their courtiers contributed to the production of high quality turbans, sashes and angarkhans. By the seventeenth century the European companies expanded Bengal’s textile trade on sea routes to three continents – Europe, America and Africa.

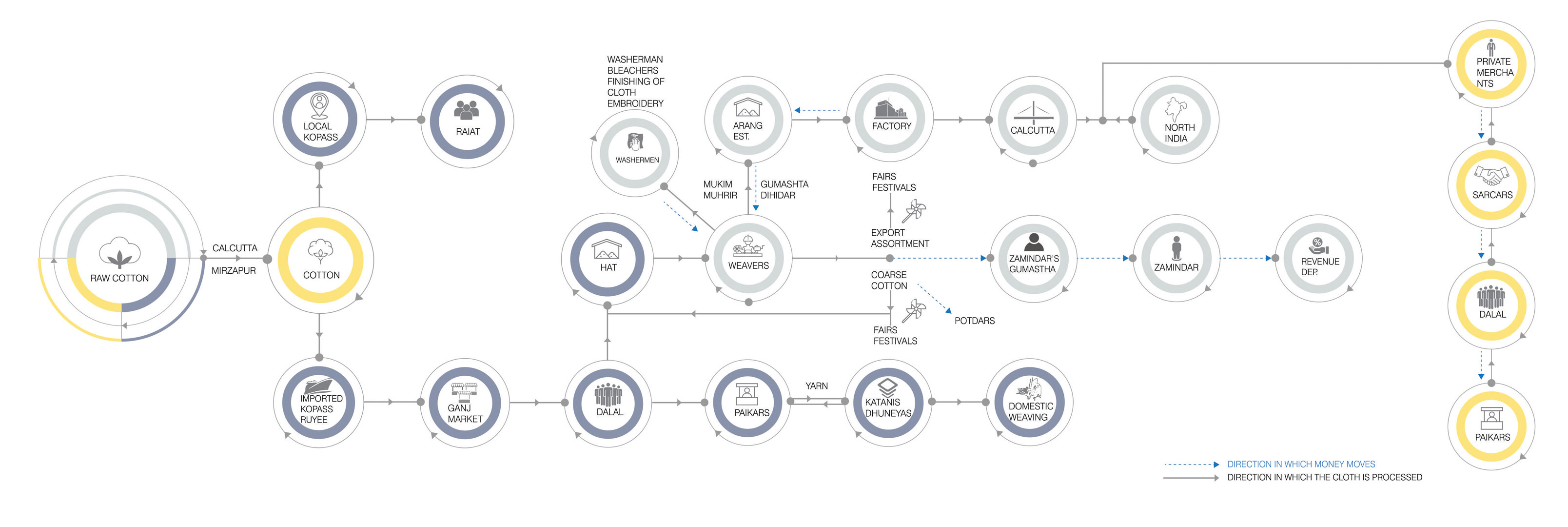

The nature of markets had a transformative effect on production as well. From simple exchanges in local weaving areas to distant markets, the traders played a significant role. Thus, we find that purchases by Arab, Armenian and Turanian traders for up country markets were made through dadan merchants, who invested their capital. The dadan system entailed payment of advances to weavers. These goods were carried on camels across to Bukhara and Samarkand. The traders brought back orders for specific designs from their buyers.

The Mughal rulers set up ‘karkhanas’ which specialised in particular assortments of cloth. Daroghas were appointed for supervision of the entire process – from checking the quality of the yarn, rolling the warp, weaving to final finishing. The tasks were strictly divided by caste, gender and age. The high-quality goods kept the weavers busy in meeting the demands of the rulers and their courtiers. Once a year a special consignment known as Mulboos Khas, which included several assortments of the finest Malmals, including Jamdani, were sent in silver caskets as tribute from the Nawab to the Mughal ruler.

By the seventeenth century the overland trade was being overtaken by a much larger demand in Europe and later America. This highly competitive trade also coincided with military conflicts between European trading companies. The Portuguese were the first to set up a factory in Hoogly in 1536. They were followed by the Dutch at Chinsurah (both in West Bengal) and Danes in Srerampur. The English East India Company started its trade in textiles in 1651 and received a Farman from the Mughal Emperor for preferential trade in 1717. Its factory at Dhaka set up an elaborate system connecting to at least eight arangs around Dhaka. It took two years for completion of orders, between the time samples were first approved by the factory and sent to the Company’s Board of Directors in London. On their approval, orders were transmitted to the gumashta, who represented the factory resident in the arang.

As competition between the European Companies and private merchants increased, the English East India Company changed its procurement system to increase its direct control over production. By 1753 dalals were replaced by gumashtas appointed by the Company to supervise production in the arangs. Financial control was maintained through advances that indebted weavers to the Company. Finally, in the second half of the seventeenth century, the Company introduced a set of Regulations for Weavers which tied them down to the Company’s trade and limited their access to other weavers. As long as weavers were free to accept advances from several buyers, they had little shortage of capital and were able to meet multiple demands. But as the East India Company acquired a monopsony it curtailed the weavers’ freedom of production through its financial and legal controls.

This was a major reason that weavers were reluctant to obtain orders from the Company. But there were other reasons for the decline in weaving. In 1770, devastating floods followed by famine affected the community’s production capacity, as cotton growing lands were turned to rice crops. Another reason was that industrial manufactures in England reduced dependence on imports and also led to reversed exports to India and other colonies.

After the Dhaka Factory was closed in 1817 and the East India Company was taken over by the Crown in 1833, the weavers of Dhaka continued to export through private merchants. They also met the local consumer demand for saris. Fine cotton Jamdani saris remained a popular item amongst middle class and upper class women, particularly in Bengal, as can be seen in photographs of women in the Tagore household. Mahatma Gandhi’s Satyagraha movement also spiked their interest in using handmade and hand spun cloth and to reject machine made cloth from Lancashire. Thus Jamdani could have gained popularity as a symbol of protest.

In the twentieth century Jamdani weavers were faced with the consequences of political disturbances during the Partition of India in 1947 and a nine month war of independence in 1971. The division of Bengal leading to the migration of an affluent Hindu clientele in West Bengal closed an important market for Jamdanis.

During the war, weavers suffered damages to their homes and looms. It also contributed to a disruption in raw material supplies. To overcome these shortages the Government introduced mechanisms for supply of credit and raw materials to weavers. More recently, in 1996 BSCIC set up a Jamdani village in Sonargaon housing for weavers’ families. Consumer demand, designers’ interests have contributed to revive and sustain this cottage industry.

Exhibitions of Bengal Textiles

It is interesting to note that even after a decline in European trade the tradition of Jamdani did not fade away. In fact, many fine samples were displayed at special exhibitions held in European capitals showing the finest varieties of piece goods from Bengal. The Crystal Palace exhibition in London in 1851 drew a lot of visitors including Queen Victoria and Charles Darwin. John Forbes Watson’s idea of ‘portable industrial museums’ led to the publication of The Collections of the Textile Manufactures of India in 1866. Eighteen volumes of mounted and classified samples of Indian textiles contained seven hundred samples in all. These illustrations were mainly taken from textiles shown at the Paris International Exhibition in 1855. More recent exhibitions in London have highlighted the significance of handloom weaving in Bangladesh and shown examples of fine Jamdani weaves.

The Jamdani Festival exhibition follows these initiatives by drawing attention to the tradition of Jamdani weaves and the artistry of the weavers. This exhibition is proud to display swatches of diverse designs and varieties of figured fabrics as examples of the craftsmanship of Jamdani weavers.

Glossary

Arangs Local centres of production

Buli Oral directions sung by the master weaver

Charkhi Wooden instrument used to clean cotton

Dadan Advance given to weaver with order; dadan merchants who gave advances

Dalals Agents or middle men who procured assortments

Daroghas Officials who supervised production

Farman An imperial decree or order

Gumashtas Agents employed by the buyers

Julaha Muslim caste of weavers

Karkhanas Workshops set up for production for the Mughals

Malmals Original name for Muslin

Malboos Khas Annual tribute to the Emperor sent by the Nawab; the finest handloom cloth and other gifts were packed in a silver casket

Natai Spindle

Shagrid Persian for student or apprentice

Shana Reed for holding the warp yarn

Satyagraha Civil disobedience movement started by Mahatma Gandhi

Piece goods Names of assortments purchased by the Company

Names of some (1) motifs and (2) patterns

(1) Bagnoli and Kalka

(2) Buteh, Jal, Terchi

Dr Hameeda Hossain is the author of Company Weavers of Bengal: Textile Production for the East India Company 1750-1813 and Working Conditions of the Company Weavers in Dhaka Arangs. She has written extensively on human rights and women’s issues in Bangladesh, particularly on workers in garment export factories, in handicraft production and migrant workers. She is a member of Ain o Salish Kendra, a human rights resource centre, and currently vice chair of Research Initiatives Bangladesh (RIB).